Authors note: I chose to not feature any images of the victims of any violence I wrote about in this post after some consideration, reasoning regarding this choice can be found in the footnotes.

For a long time, but especially in the last year or so, I have found great comfort in learning about horrible things. Fiction, occasionally, but more often than not I will choose to enter a rabbit-hole of disturbing historical narratives, human cruelty, and tales of systematic oppression and hate. After the election in November, I was surprised when I found myself unable to consume most content. There were a handful of things I could sit through watching, but overall, I usually found myself feeling constantly on edge and exhausted all at once. I often would say I felt like my “brain was dying”, a feeling of numbness and a desperate need for something despite feeling simultaneously overwhelmed and underwhelmed. This feeling would only dissipate when I would dive into learning about the horrors of the world, desperate to understand why things are the way they are. I would save article after article, creating a stockpile of content on Zotero that chronicles various topics that caught my eye. Some categories include “MAGA Kitsch”, “Weird patriotism”, and “Human Spectacle/Plastic Surgery”, My writings on this very website catalog this exploration to a large extent. I’ve spent hours reading about racist transhumanist men that believe in eugenics, MAGA’s clear parallels to the Nazi regime, Televangelists spewing hate and scamming viewers out of money all in the name of Christ, and more generally how throughout all of history there have been horrible people doing horrible things time and time again.

Despite being drawn to seek out this sort of upsetting content, I began to find myself unable to stomach the images I was seeing on social media. I felt drained, depressed, helpless, but I could not stop scrolling. This began back in 2023, after October 7th. As an American Jew with deep roots to my community, I’ve had a long, complicated, and critical relationship to Israel. I never identified as a Zionist but was raised in a community where doing so was the norm (Jewish day school, overnight summer camp, youth group.) It is because of, not in spite of, my Judaism that early on, less than a week after the genocide in Gaza began, I became active in organizing with a pro-Palestine Jewish organization. It felt important; it was important. Through all this I was constantly inundated with inhumane crimes being committed in the name of a community I have always held dear, constantly disappointed in people I expected better from, and constantly horrified by what I saw. An incessant, endless barrage of images. Desiccated children, of homes destroyed, of human suffering and annihilation. I looked at them, many times a day. They were shared on social media, they were discussed in Signal, they were on the news. My family constantly sent articles; I constantly sent articles. “It is important for me to look” I told myself, “It is important for me to witness.” So I did, everyday, for months.

And then there were the posts by people I grew up with. Some posted videos of the attacks by Hamas on October 7th, some defended Israel’s violence, dismissing people like me, who believed in Palestinian liberation, as fundamentally hateful. I remember, one evening, logging on to Facebook (my first mistake). There, on my timeline, was a post by a man that I had met once while in a Jewish youth group in high school. Like quite a few people I know, he had made Aliyah (moved to Israel) and was serving in the army. He had posted a photo album of his time in Gaza, depicting it like some sort of fun romp. Here was this American man, a man with no more of a right to that land than myself, lounging on a couch in a home that belonged to someone in Gaza, a gun strapped across his chest, his feet in combat boots resting on a coffee table, a grin on his face. Someone, maybe even a family, had lived in that home. Maybe they had fled, maybe they had been awakened in the middle of the night and forced out by soldiers to use their home as a base, maybe they had been detained, maybe they had been killed. And here was this American man, a man that grew up in Los Angeles, just like me, smiling at the camera, in a uniform for an army I had been encouraged to support my entire life, posting on Facebook while Palestinians were being slaughtered. There was no graphic violence in the image, no blood, no gore, but the disgust and anger I felt was overwhelming. I blocked him and logged off. I can still see the image in my head and feel the same disgust I felt then. It has been almost two years.

After this, I kept looking. I watched and shared and looked and scrolled. Everyday, multiple times a day, from the moment I woke up and checked the news, to when I went to bed scrolling on Instagram, I looked. “I have to look, it is my duty to look,” I told myself. This insistence on looking was not something new. As a high schooler, I bought myself a copy of Mein Kampf because I thought it was important to understand, to hear it from the horse’s mouth: why Hitler insisted people like me were so horrible. I remember asking my mother why she would not watch films about the Holocaust and why she had no interest in visiting the Camps. “It is upsetting to see because it is important.” I remember insisting, “You should feel upset; if you are not upset you are not looking hard enough.” She would agree that it was important but tell me that she already knew about the suffering and horror. What does watching it do if she is already aware, if she has seen it before. What more would it do than cause distress? “But we should be distressed!”, was my reply.

These were images of the past, a past that to me felt much farther away than it truly was. They were seen in specific environments with context that I could predict, in a classroom or a textbook or in a documentary. I knew what I would see because we all knew what happened. We knew of the starving, of the torture, of the violence, of the death. The photos, though horrible, felt like historical artifacts to me then, black and white and untouchable: important, of course, but something that happened before me. I had seen them many times, or some version of them in some way or another. The piles of shoes, the barracks, the gaunt faces, the mountain of human bodies. It was a familiar suffering. I knew it was real, but it was also the past. We looked at them, I insisted, because we needed to remember.

Seeing suffering in real time, however, is something else entirely. Since the invention of the printing press, then photography, and then television, humans have become more and more aware of the world around us, for better or for worse. In the early 1860’s the French poet Baudelaire wrote the following in his journal;

It is impossible to glance through any newspaper, no matter what day, the month, or the year, without finding on every line the most frightening traces of human perversity... Every newspaper, from the first line to the last, is nothing but a tissue of horrors. Wars, crimes, thefts, lecheries, tortures, the evil deeds of princes, of nations, of private individuals; an orgy of universal atrocity. And it is with this loathsome appetizer that civilized man washes down his morning repast.1

When I read this the first time I was in awe. If he felt that way then, he could never imagine now. Now we see it all the time. Now it is not just words or descriptions but videos on a screen, on a television, in my pocket. Now I will be scrolling through Instagram and go from a meme of J.D. Vance, to an engagement announcement, to a city destroyed by war, to a video of a baby and a dog, to a recipe picture, to a young girl sobbing explaining that her parents went to get food and never returned. I sit on my couch across the world and watch a man in the West Bank tell me about the bombs going off in real time. I watched my home burn down in news clips; I watched the Capitol be pillaged by red faced men spewing hate; I watched police violently attack protestors and kill unarmed black men. I can look at Google Earth images of Gaza in 2023 and compare them to now. I can see the destruction from an aerial view.

I sit on my couch across the world and watch a man in the West Bank tell me about the bombs going off in real time. I watched my home burn down in news clips; I watched the Capitol be pillaged by red faced men spewing hate; I watched police violently attack protestors and kill unarmed black men. I can look at Google Earth images of Gaza in 2023 and compare them to now. I can see the destruction from an aerial view.

Images of war, destruction, and human suffering are not new, but how the images are disseminated has evolved. Vietnam, often called “the television war” or “living room war”, was the first time in history that the public could see, more or less, daily updates about a war occurring across the globe in the comfort of their own homes on television screens or on the pages of magazines. There are various arguments regarding how much this impacted the American public’s views about the war itself (some say the media influenced the public perceptions to shift towards anti-war, others argue that the public influenced the media, a classic chicken or the egg situation), but regardless of this issue, there is no argument that this was the first time these types of images were so widely and consistently available in day to day life. The nature of the war itself also allowed for a new type of coverage. As Alex Burmaster explains in his article “Shooting Both Sides”, “Vietnam provided a unique set of opportunities. The loose nature of the conflict and the confusion of the battlefields allowed photojournalists unprecedented free rein. It was an unusual war in that photographers (except those working for the communist North) did not have to represent a particular side.”2 Because of this, and the new technology that allowed for more of the public to see images of war, Americans became increasingly aware of the violence and horror taking place in Vietnam.

For many, this type of coverage made the war feel more real. To see images and video of real life events served as a reminder of what was occurring, despite it not taking place on American soil. However, it also allowed for a distancing of sorts. In an article for the New Yorker in 1966, Michael Arlen suggested that perhaps, the televised nature of the war actually allowed the viewer to distance themselves more than we acknowledge. He wrote;

I can't say I completely agree with people who think that when battle scenes are brought into the living room, the hazards of war are necessarily made "real" to the civilian audience. It seems to me that by the same process they are also made less "real"—diminished, in part, by the physical size of the television screen, which, for all the industry's advances, still shows one a picture of men three inches tall shooting at other men three inches tall, and trivialized, or at least tamed, by the enveloping cozy alarums of the household.3

Is it possible that both can be true? That this new coverage of the Vietnam war made it seem more real and at the same time something unreal for viewers? Photography (and in this instance, I am using the term not to just describe still images but video as well), is full of these seemingly incompatible truths regarding what is and is not “real”. Because of the technological aspect of the craft, it has long been viewed as not only an art form but a way of documenting evidence and truth. Unlike painting or drawing, photographs are a snapshot of an event, a captured image of what someone sees. But there is always a person behind the lens, and there is always someone choosing what images are showcased. Sontag describes photographs as somehow objective and also personal in Regarding the Pain of Others, stating that they can be “both objective record and personal testimony, both a faithful copy or transcription of an actual moment of reality and an interpretation of that reality…”4

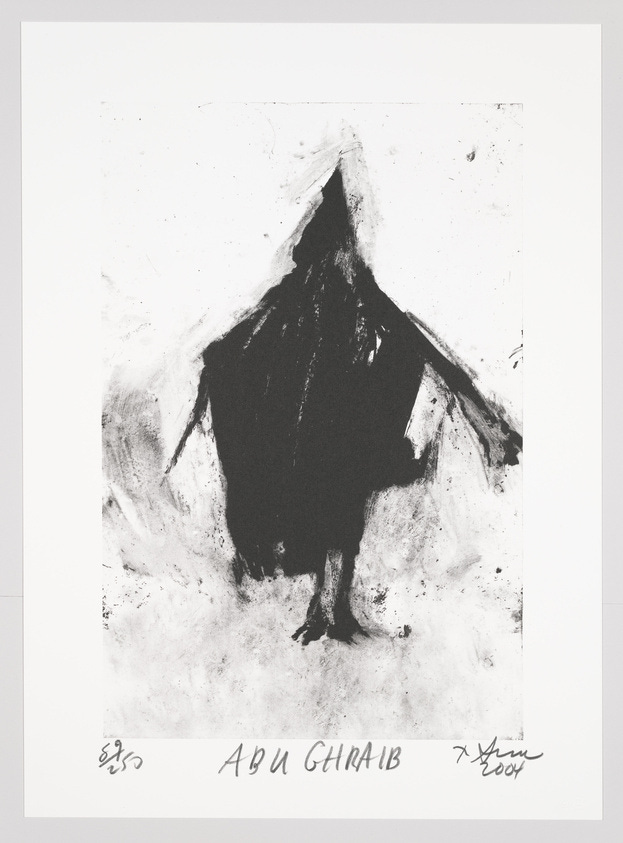

Since Vietnam, we have seen another shift in the documentation of war; before, the images the public saw were taken by photographers, now, almost everyone involved has access to a camera. During America’s Global War on Terror, U.S. soldiers began to document the violence of war from their perspective. These photos were not taken to serve the same purpose as the images captured by photojournalists in Vietnam, meant to document and showcase war to the public. These were something else entirely, more akin to souvenirs or trophies. In April 2004, the public saw exactly what these photos and videos consisted of when the media published images and video taken at Abu Ghraib prison in Iraq. They showcased horrific, criminal, and inhumane treatment, torture, and sexual abuse of Iraqi prisoners by American troops. Oftentimes, soldiers would be posing with the prisoners as if they were not human but an object, grinning with their thumbs up as they carried out horrific acts of cruelty under the guise of patriotism. This was not an isolated incident. In 2010, thousands of photographs and videos were uncovered, all taken by a group of American soldiers, self labeled “the Kill Team”, chronicling the violent abuse, torture, and ultimate murder of civilians while stationed in Afghanistan. Similar to the images taken at Abu Ghraib, these soldiers were seen grinning ear to ear while posing with victims of their senseless (and most definitely racially motivated) violence.

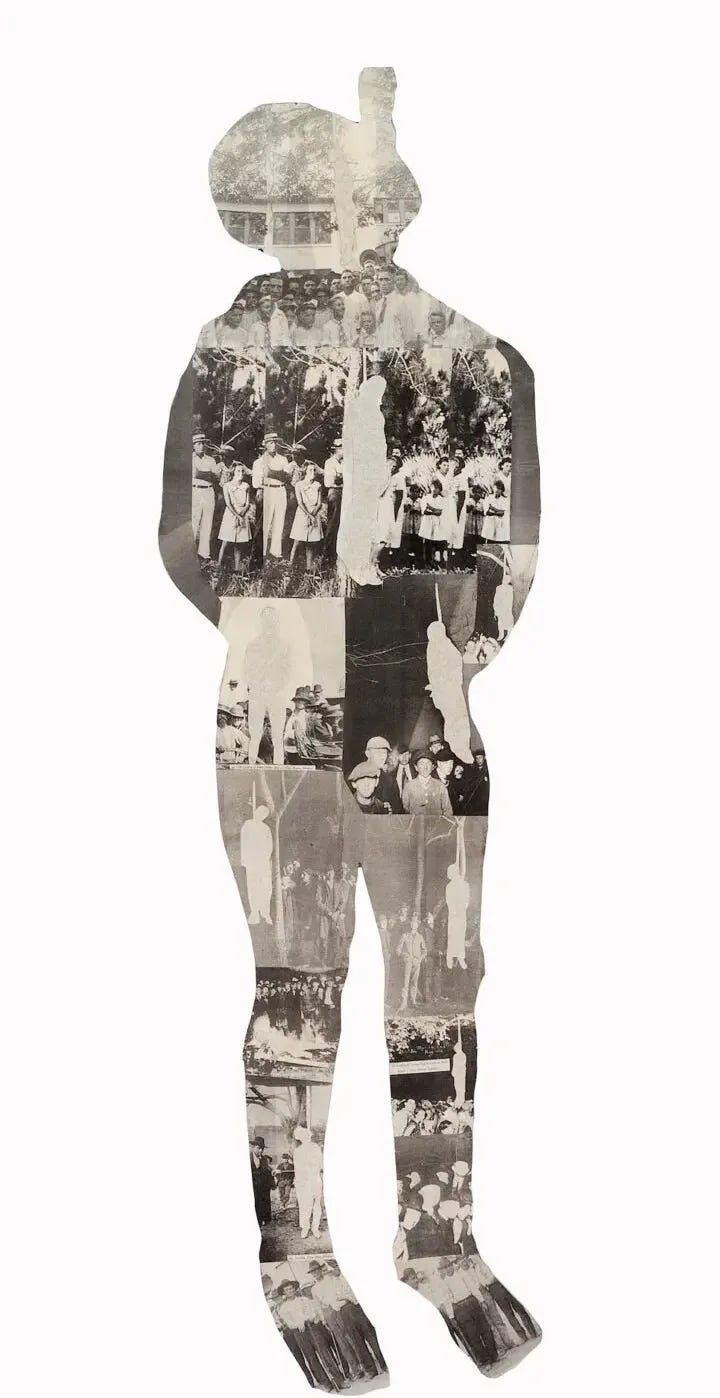

Who were these taken for? As I looked through these photos while researching, that question kept coming to mind. Many of them resemble the type of images you’d see someone capture on vacation, striking a silly pose with some monument, a photo you’d come home and put in a scrap book or send to your family in an email to let them know you were enjoying your trip. But is that what they were? Were they meant to share with other soldiers, were they meant to be kept as a private memento, were they taken with any actual forethought at all? They were certainly not images the soldiers photographing and being photographed planned for the public to see, that is clear. Much has been written about these images since their initial release over twenty years ago. One parallel often made compares the photos of Abu Ghraib to the photo postcards and souvenirs of lynchings from the late 19th to the early/mid 20th century. In many ways, it is an apt comparison. Both showcase white Americans witnessing or carrying out violence against black and brown bodies as entertainment. Both dehumanize the victim, turning a person into a spectacle and object to dominate, something the act of photographing only enhances. As Sontag describes, “Photographs objectify: they turn an event or a person into something that can be possessed.”5 But it is not only that these images objectify. Part of the horror and cruelty of both the Abu Ghraib and lynching photographs is that they were taken at all. To imagine that someone would perpetrate such acts of violence and feel the need to document it, to celebrate it, to smile at a camera, to capture the moment, adds a new level of cruelty to the violence. In Regarding the Pain of Others, Sontag describes this in relation to the photographs of lynching, but it also easily applies to the images of Abu Ghraib and the Kill Squad:

Intrinsic to the perpetration of this evil is the shamelessness of photographing it. The pictures were taken as souvenirs and made, some of them, into postcards; more than a few show grinning spectators, good churchgoing citizens as most of them had to be, posing for a camera with the backdrop of a naked, charred, mutilated body hanging from a tree. The display of these pictures makes us spectators, too.6

But we are no longer just spectators looking at these images from a strictly observational view. Another technological advance soldiers have brought onto the battlefield has allowed us to experience war zones from a first-person perspective in our homes; GoPros. While this technology did exist during the Global War on Terror, it has become increasingly popular in its use during the ongoing Russo-Ukraine war. When I searched “gopro combat footage”, I found video after video of the war in Ukraine shot in first-person, making it feel as though I was there experiencing it. Uploads spanning over an hour with text describing the events on screen, Youtube shorts with voiceovers analyzing the footage, TikToks, a vast archive of footage all from the soldier’s literal perspective. This content is not niche, one channel that pops up when you search has over 1 million subscribers on Youtube with videos that are well over 10 million views.

This type of documentation has the effect of making the war both more real and less real for viewers, just as Arlen described regarding the coverage of Vietnam. On one hand, videos like these, and social media overall, play a huge role in modern warfare and politics today. People around the world have arguably become more aware and more invested in the Russo-Ukraine war because of this type of content in a way that they most likely would not have if it were only seen from a distance on the nightly news. The first person perspective and chaotic footage feels more real than a sanitized depiction of war, more authentic, and viewers connect with that. In the book Graphic: Trauma and Meaning in Our Online Lives, Alexa Koenig and Andrea Lampos describe the difference between traditional coverage of these types of events in comparison to first-hand videos:

This open-source content is intimate by nature: a video shot in the midst of a human rights violation may not only show us blood and death but may expose us to expressions of a person’s terror in the moment, their breathy commentary and anguished cries. Some of these raw videos can bring us into the experience in a direct and painful way – more so than an edited and packaged newscast.7

All of this is true, and yet, when I look at the comments on these GoPro videos, it is clear that for many members of the audience, the combat is still “unreal” to some degree, or, at the very least, still seen as a form of entertainment despite the logical understanding of it being real. Some viewers say how odd it is to be living in a time where a soldier is outright vlogging warfare to post online, others compared it to Call of Duty or other similar first-person shooting games, some even called out a specific figure seen in the video a “fucking legend” for providing soldiers in the videos Redbull and Vodka during wartime. It is an odd array of spectators aware of how real the war they are watching is while also creating distance in various ways. “This is so surreal.” One comment with over 1 million likes reads, “My brain keeps making me think it’s just a game or movie. The fact these are real people, fighting and dying in an actual war is something it doesn’t seem to want me thinking about.”

In the first essay of “On Photography”, Susan Sontag wrote the following,

To suffer is one thing; another thing is living with the photographed images of suffering, which does not necessarily strengthen conscience and the ability to be compassionate. It can also corrupt them. Once one has seen such images, one has started down the road of seeing more––and more. Images transfix. Images anesthetize. An event known through photographs certainly becomes more real than it would have been if one had never seen the photographs... But after repeated exposure to images it becomes less real.8

Is it really inevitable to become less and less affected by these types of images if they are so prevalent in our day to day lives? I do not feel numb, or, not truly numb, nor am I truly disaffected. If I were, wouldn’t I be able to continue living unaffected by the horrors I witness virtually? I could see them, put my phone down, and continue my day as usual. And yet, isn’t that exactly what I do? I often scroll past, maybe affording a “like” to acknowledge that I have witnessed it, but I do keep scrolling, usually. I do not break down in tears upon seeing these types of images, but I do feel something. Is it the vast number of images I see, or is it the way they are being presented that is the larger issue?

There is something surreal about seeing these images so often and in quick succession between lipgloss ads and posts from meme pages on Instagram. In Ways of Seeing, John Berger describes the whiplash of seeing advertisements, what he calls “publicity’s interpretation of the world”, in contrast with the reality of global conditions in magazines. “The shock of such contrasts is considerable: not only because of the coexistence of the two worlds shown, but also because of the cynicism of the culture which shows them one above the other.”9 This stands true, if not even more true, in the social media age. Through apps like Instagram and TikTok we see more of these images on a day to day basis, often in quick succession. Our interactions with them are often shorter than they would be if it were in a print magazine where there are only so many images to look at, often visually buffered by text. Instead, these photos and videos are often short-form, sandwiched between countless other posts unrelated to the horrors of real life. This, in turn, shifts our own reactions to the content. In order to understand what we are seeing, to make any sense of it, you would need to muster the attention to watch an entire video and not just the snapshot, perhaps click a link and read an article or multiple. When we are inundated with content, to interact with it meaningfully requires energy and effort. It is exhausting to constantly see horrible things, and it is understandable that one would simply feel the desire to keep scrolling instead. However, simply glancing at an image of an atrocity does affect us, or at least, it affects me.

I do not break down in tears upon seeing these types of images, but I do feel something. Is it the vast number of images I see, or is it the way they are being presented that is the larger issue?

In her essay “Reflections on Images of Violence”, director Natalia Almada describes this type of digital witnessing as “(dis)engagement”, stating that the whiplash John Berger wrote of in magazines has become a part of our daily reality– we are constantly confronted with violence and horrors occurring while simultaneously going through the minutia of daily life. This (dis)engagement prevents us from being fully present in our “real life”, understandably affected by the images we see on our screens, while also being unable to fully empathize or reckon with the horrors being shown to us virtually. Almada writes,

I may be picking up my kid from school when an image of the war in the Ukraine appears on my phone. That image lingers in my mind when I kneel down and open my arms to catch him running towards me. What does this do to us? How does it impact the way we relate to our present and to each other? I am neither able to receive my child’s joy full-heartedly, nor am I able to empathize with the Ukrainian people under attack. Images have lost their power to move us because they do not command our full attention.10

Is it possible that we have lost the ability to be moved by these types of images? I personally do not think so. Images have a power over us, and they serve an incredibly important role, but for that power to be harnessed we must do more than just glance, otherwise we simply feel helpless and ultimately experience the type of (dis)engagement Almada describes. When we look at these sorts of images without fully taking the time to reckon with what we are looking at, when we do not truly give them our full attention, we inevitably are left with a feeling of apathy.

When we are inundated with content, to interact with it meaningfully requires energy and effort. It is exhausting to constantly see horrible things, and it is understandable that one would simply feel the desire to keep scrolling instead. However, simply glancing at an image of an atrocity does affect us, or at least, it affects me.

While researching for this essay, two quotes analyzing our supposed numbness to images of suffering struck me. The first from Sontag reads,

Compassion is an unstable emotion. It needs to be translated into action, or it withers… People don't become inured to what they are shown–if that's the right way to describe what happens– because of the quantity of the images dumped on them. It is passivity that dulls feeling. The states described as apathy, moral or emotional anesthesia, are full of feelings; the feelings are rage and frustration.11

Sontag claims that the quantity of images or information is not related to this issue, but I disagree. Regarding the Pain of Others was published in 2003 before the growth of social media and smart phones. While this may have been the case then, things are not the same in 2025. It is not only the quantity of images that affects us but their universal and immediate accessibility. As Almada describes, “The mobility of the images on our portable devices allows them to insert themselves into our lives at any time, any place, any moment. There is no containment. They invade us not only when we look at our devices but by the knowledge that they are there waiting for us to decide whether or not to look”.12 The type of passive engagement Sontag is describing is more prevalent now than it was in 2003 because of this mobility and the overwhelming amount of content, making it easier to fall into apathy.

The other, a quote from Dr. Naomi Remen, builds upon this idea of apathy being a shield for something else.

The expectation that we can be immersed in suffering and loss daily and not be touched by it is as unrealistic as expecting to be able to walk through water without getting wet. This sort of denial [of our experiences] is no small matter. The way we deal with loss shapes our capacity to be present to life more than anything else. The way we protect ourselves from loss may be the way in which we distance ourselves from life and help. We burn out not because we don’t care but because we don’t grieve. We burn out because we’ve allowed our hearts to become so filled with loss that we have no room left to care.13

When I reflected on these ideas I understood my own feelings in a new way. What I had often described as “my brain dying”, the apathy, and the simultaneous feeling of being both over and underwhelmed, were all signs of something else. It was anger, frustration, hopelessness. The amount of horrible things occurring all at once, my awareness of them, and the (dis)engagement I often have with these images has led to an inability to truly process or grieve. I had conversations about this early on after October 7th with friends and family about how it felt impossible to grieve when grief just kept happening. Even now it is still happening. It is not easy to process when we are constantly being made aware of more atrocities that we have to grieve.

Photographs by nature are snapshots of a much more complicated bigger picture. An image without context may shock us, but the power of an image lies in that it makes the viewer engage. When our engagement with these images are in more controlled environments like during a television news segment or in a newspaper article, more context is provided, a story forms and we are able to make meaning. Often on social media, we experience images quickly, perhaps we will pause and look closer, but rarely do we take the time to truly process an image. Sontag describes “image-glut” in relation to television, but the sentiment is even more pertinent when applied to social media:

Image-glut keeps attention light, mobile, relatively indifferent to content. Image-flow precludes a privileged image. The whole point of television is that one can switch channels, that it is normal to switch channels, to become restless, bored. Consumers droop. They need to be stimulated, jump-started, again and again. Content is no more than one of these stimulants. A more reflective engagement with content would require a certain intensity of awareness––just what is weakened by the expectations brought to images disseminated by the media, whose leaching out of content contributes to the deadening of feeling.14

Images have power, and this is not a bad thing. They transcend language, they stick with us, and they can lead to real change. But our engagement with them must be intentional. There is a difference in looking at these types of images for a reason, with forethought and intention, versus seeing them and simply engaging on a superficial level, often leaving us to feel hopeless and numb. In order to keep ourselves from becoming passive spectators, we must make an active effort to engage. To quote Sontag, yet again, for the final time (at least in this essay),

“The ultimate wisdom of the photographic image is to say: 'There is the surface. Now think––or rather feel, intuit––what is beyond it, what the reality must be like if it looks this way.'”

I no longer feel it is my duty to simply look, I want more. I want to feel, to think, to grieve, to see beyond the image and notice the full picture instead.

Charles Baudelaire, Intimate Journals, tr. 1990

Alex Burmaster, Shooting Both Sides, New Statesman, July 16, 2001

Michael Arlen, Living-Room War, The New Yorker, October 15, 1966 P. 200

Sontag, Susan. 2003. Regarding the Pain of Others.

ibid. Sontag, Susan. 2003. Regarding the Pain of Others.

ibid. Regarding the Pain of Others.

Koenig, Alexa; Lampros, Andrea. Graphic: Trauma and Meaning in Our Online Lives (p. 5).

Sontag, Susan. (2008). On Photography. Penguin Classics.

Berger, John. (2008). Ways of seeing. Penguin Classics.

Almada, N. (2023, March 1). Reflections on Images of Violence | International Documentary Association. Ida: International Documentary Association. https://documentary.org/feature/reflections-images-violence

ibid, Regarding the Pain of Others.

ibid. Almada

ibid. Koenig

ibid. On Photography.

Authors note cont: These images are easily findable if you feel the need to seek them out, but after writing this and reflecting I felt that there was no need to include them in this essay, especially since the entire piece is discussing how we should engage with these types of images with intentionality. This specific Sontag quote was a large influence on o this decision, so I will include it here.

What is the point of exhibiting these pictures? To awaken indignation? To make us feel 'bad'; that is, to appall and sadden? To help us mourn? Is looking at such pictures really necessary, given that these horrors lie in a past remote enough to be beyond punishment? Are we better for seeing these images? Do they actually teach us anything? Don't they rather just confirm what we already know (or want to know)?

Really love this piece! Information overload is a growing problem our generation has to grapple with, often having to choose between full exposure to everything everywhere all at once or total disconnection (a duality that turns out to be false). This articles wonderfully contextualizes this in the history of visual information (crazy how authors cautioned the disaffectedness that comes from this overload as far back as Baudelaire), and I really appreciate the contextualizing shared in Sontag's words on how to still live our values in a meaningful way that transcends the duality.

“The ultimate wisdom of the photographic image is to say: 'There is the surface. Now think––or rather feel, intuit––what is beyond it, what the reality must be like if it looks this way.'”