Gilded everything, ornate recreations of Corinthian columns, an indoor fountain made of marble, a glass tabletop supported by a statue of three golden cupid-children holding hands. So bad it’s good, so good it’s bad, ugly but not ugly, tasteful in its lack of taste. Kitsch. Is this a description of the infamous Madonna Inn, perhaps? No, I am describing Donald Trump’s NYC penthouse. It looks like Las Vegas, like Jeff Koons, like artifice and excess. Fran Lebowitz once described Trump as “a poor person’s idea of a rich person,” and his penthouse proves her point.

Trump’s love of kitsch is not just reserved for his multiple homes. It permeates throughout the MAGA/conservative movement: schlocky oil paintings depicting Trump as a Christ-like figure saving little white children, an AI image posted by official White House social media accounts depicting Trump on the cover of Time Magazine with a shit-eating smile donning a crown captioned “LONG LIVE THE KING,” the WWE; his steak business, Mar-a-Lago; overpriced teddy bears wearing tiny bathrobes with “Trump” embroidered in gold thread. Some may argue that taste is nothing more than a preference—choosing blue over green or favoring stripes over florals. But Donald Trump’s panache for kitsch is not a simple preference; it is the foundation of his brand, and aesthetics, like everything else, are political.

Kitsch, like camp, is more than an aesthetic descriptor; it is a way of being. In his seminal 1929 essay “Avant-Garde and Kitsch,” Clement Greenberg wrote,

Kitsch is mechanical and operates by formulas. Kitsch is vicarious experience and faked sensations. Kitsch changes everything according to style but remains always the same. Kitsch is the epitome of all that is spurious in the life of our times. Kitsch pretends to demand nothing of its customers except their money—not even their time.1

None of this description describes an aesthetic, instead focusing on the feeling it evokes, not a defined look. In his work, Greenberg laments the shallowness of kitsch, the commercialization, and the faux-sentimentality. The type of art objects that are often categorized as “kitsch” are usually mass-produced and feel overly sentimental–think “Precious Moments” collector figurines or Thomas Kinkade paintings of glowing cottages and rainbow landscapes. They are the types of art you would imagine a stereotypical grandmother having in her home, the sort of artwork she may look at and say, “Look how sweet, how pure, how lovely.” They make the viewer feel something, maybe a longing or sense of nostalgia for a world that never existed in the first place. The feeling is real, yet shallow, stirred by visual cues meant to trigger sentimentality. Kitsch aesthetics and rhetoric do not ask the observer to create meaning in order to then feel an emotion; instead, they directly tell them how to feel.

Greenberg illustrates this phenomenon by comparing the artist Pablo Picasso, representing the avant-garde, to Ilya Repin, a renowned Russian painter during the 19th century, representing kitsch. “Where Picasso paints cause, Repin paints effect,” Greenberg states, arguing that while Repin “predigests” the meaning of the work for the viewer, Picasso’s requires the viewer to project and make meaning. Kitsch, Greenberg contends, is “synthetic art,” imitating the effects of the avant-garde (read as “high” art).2

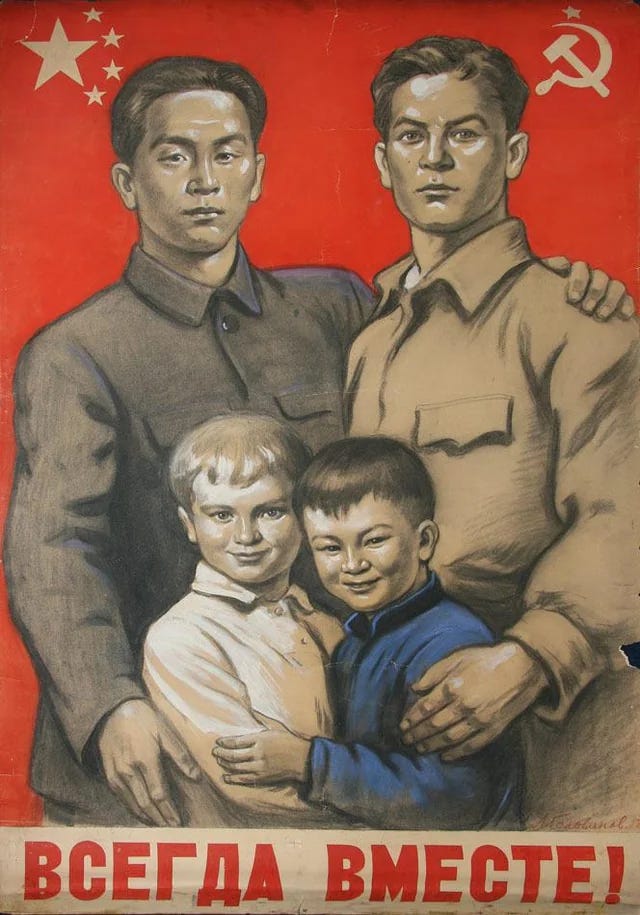

This lack of substance has come to define the aesthetic and rhetoric of the MAGA movement, but it predates Trump in the American Conservative movement. In his article “Trump the Fascist Artist: How the MAGA Crowd is Motivated by Aesthetics, Not Ideas,” Matthew Rosza argues that even before Trump’s rise to power, the conservative movement was “no longer defined by beliefs but by intense hostility towards perceived threats that they invariably attributed to the left.”3 While Rosza does not use the word “kitsch” to describe this political approach, that is precisely what it is: a removal of all substance and a reliance on emotional grabs. This method is not just used in American conservatism; it can be seen in political movements throughout history. Milan Kundra, one of the most cited critics of kitsch, wrote that “No one knows [kitsch] better than politicians… Kitsch is the aesthetic ideal of all politicians and all political parties and movements.”4 Kitsch has been used by leaders like Mao, Mussolini, Stalin, Hitler, Saddam Hussein, and Ferdinand Marcos. It can be seen in their homes, like Saddam’s marble falcon in Baghdad, in their propaganda imagery, like Stalin and Mao’s posters during the Sino-Soviet Treaty of Friendship and Alliance, and in popular culture during their rule, like this swastika ashtray and other memorabilia sold during the Third Reich. It is because of, rather than in spite of, this lack of depth that kitsch has been utilized time and time again by dictators and fascists.

Kitsch is easily accessible and takes little time and little energy to fully understand what it is trying to communicate. As a result, kitsch is often embraced by large swathes of the public. In his essay “Organizational Kitsch,” Stephen Linstead argues that one of the appeals of kitsch is that “we don’t need to be persuaded by it, just to share and participate in it is sufficient––it works without us having to think about it… Kitsch will feel for us and think for us if we are willing to let it.”5 Kitsch will tell us what is good, what is bad, what we should fear, what we should strive for, and it will do this without requiring us to think or analyze; it is presented to us right there on a gaudy, ornate, gold-plated platter. It is kitsch’s popularity and accessibility that so often lends itself to political movements. Greenberg too points out that kitsch can be seen in totalitarian regimes from Germany to Russia to Italy, “not because their respective governments are controlled by philistines, but because kitsch is the culture of the masses in these countries, as it is everywhere else. The encouragement of kitsch is merely another of the inexpensive ways in which totalitarian regimes seek to ingratiate themselves with their subjects.”6

Similarly, MAGA ideology and aesthetics rely on mass appeal and commercial familiarity. Before becoming president, Trump was a businessman, and while perhaps not a successful one, was and still is adept at creating a spectacle. He made a name for himself in reality television, celebrity, and capitalistic schtick—selling everything from vodka to a non-accredited university program. Trump is not just an individual but a brand. This approach has successfully been translated to the political sphere in the form of MAGA, where it has served Trump well. Chris Lehman writes of this branding in the article “The MAGA Aesthetic is Beginning to Rot,” explaining: “The MAGA brand is familiar to anyone who’s watched a half-hour cable TV infomercial: It’s a mass-produced, rather carelessly assembled, badge of self-improvement doubling as a pronouncement on the parlous state of the American republic. It promises the same instant boons to well-being that you’d get from B-grade TV hosts hawking diet gummies or snuggle blankets.”7 Like all kitsch, MAGA is easily recognizable and plays on the public's emotions, making grandiose promises and vapid pronouncements. And, like all kitsch, it is shallow. Lehman continues, “The fact that so much of official MAGA ideology is so deeply incoherent is testimony to the many ways that Trumpism is a brand first and a political affiliation as something of an afterthought.”8 The substance is not as important as the branding, the aesthetic, the appearance. The actual depth is insignificant, what matters are the emotions the brand/image/words stir in the observer. MAGA, like all kitsch, is all bluster, no substance.

It is because of, rather than in spite of, this lack of depth that kitsch has been utilized time and time again by dictators and fascists.

The question then becomes, “If there is no real depth to kitsch, how can it be harmful?” While kitsch itself is artificial, the feelings it creates in the observer are very real, and so-to in turn are the actions and ideas that drive wide-reaching effects. As Catherine Lugg so eloquently describes in her essay “Kitsch; From Education to Public Policy,”

Kitsch is art that engages the emotions and deliberately ignores the intellect, and as such, is a form of cultural anesthesia. It is this ability to build and exploit cultural myths - and to easily manipulate conflicted history - that makes Kitsch a powerful political construction.9

This myth building she describes can be seen in kitsch political imagery throughout history. In the article “Why Dictators Love Kitsch,” Eric Gibbs uses the example of a photograph I remember seeing years ago of Vladimir Putin riding a horse shirtless. When I first saw this image back in high school, I found it funny (I still do). It is such a blatant display of machismo, a complete performance of what is seen as “masculine”, that, to me, it reads as desperate. Just how Donald Trump is “a poor man’s idea of a rich person,” these images of Putin are what a little boy would imagine a “real man” to be: a shallow, performative caricature. However, there is more to this image than that. Gibbs writes, “All political leaders try to project an image of vitality and vigor, but these photos went farther in their attempt to portray Mr. Putin as somehow superhuman. As such, they are of a piece with the propagandistic purposes of totalitarian kitsch in which the leader is turned into a larger-than-life icon.” He goes on to compare this photograph to an image of Hitler as a knight in shining armor and of Mao Zedong's public swimming excursion in the Yangtze River. Gibbs explains that these types of images are “designed to portray the respective leaders as Canute-like figures, so powerful they could even master the forces of nature.”10

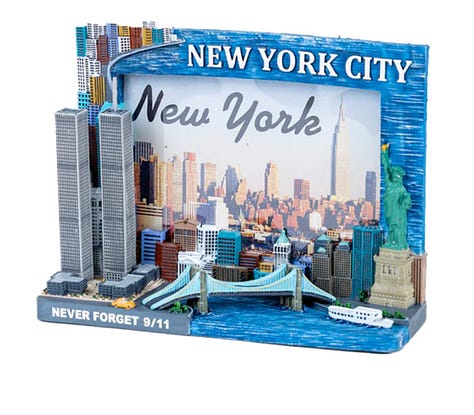

As Lugg states, kitsch can be viewed as “a form of cultural anesthesia,” a way of completely changing the narrative of history through emotional engagement. While the images of Putin, Hitler, and Mao portray them as strong and heroic, kitsch can also be used to create an air of innocence and naivete. Like Linstead states, “It [kitsch] prettifies the problematic, makes the disturbing reassuring, and establishes an easy (and illusory) unity of the individual and the world.” This type of cultural anesthesia and rewriting of history can be seen in how America and Americans choose to depict ourselves and the nation in relation to the rest of the world.

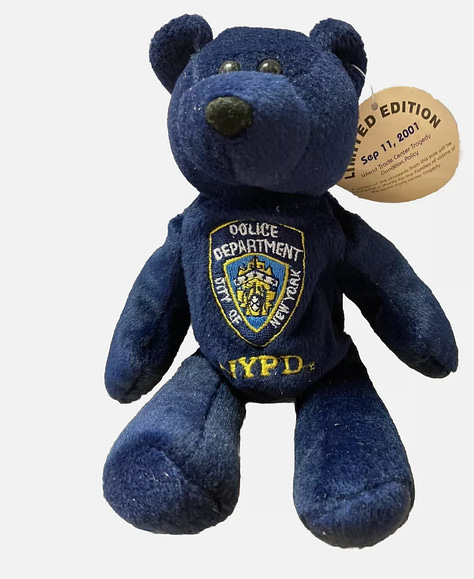

In her book Tourists of History: Memory, Kitsch and Consumerism from Oklahoma City to Ground Zero, Professor Marita Sturken argues “that kitsch is the primary aesthetic style of patriotic American culture” and describes how this type of patriotic kitsch is tied to the “renewed investment in the notion of American innocence.”11 This depiction of American culture and history allows for a type of distancing at best and a complete victim complex at worst. John Frow builds on Sturken’s ideas in in his essay “Kitsch Politics” where he discusses this false idea of American innocence and how it is “bound up with a systematic disavowal of the exceptionalist underpinnings of America's role in the world: the 'why do they hate us' syndrome (to which the implied and often explicit response is: 'because they hate freedom we embody'; they hate us because we are virtuous'). That self-representation as innocent is bound up with certain kinds of kitsch sentimentality––the teddy bears that swamped the Oklahoma site, icons for firefighters in New York—which are at once comforting and infantilizing and which allow its proponents to understand themselves as incomprehensible evil.”12

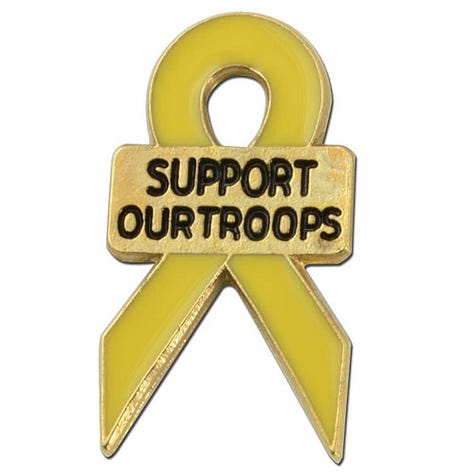

The use of kitsch to deny responsibility brings to mind a quote from Milan Kundera’s novel The Unbearable Lightness of Being, “kitsch is the absolute denial of shit, in both the literal and figurative sense of the word.” This attitude of refusing to acknowledge any grey area, any wrongdoing, or, as Kundera describes it, “shit,” leads to a victim complex that often thrives in a capitalistic structure. Hal Foster wrote of this type of “humble kitsch” during the post-9/11 Bush era in his essay which argues that these types of kitschy goods were tokens used to beautify the war on terror, to ignore the violence and death in favor of nationalism. Using the example of yellow ribbon decals showcasing support for US Troops, Foster writes,

The point is not to mock this symbol (its shallowness belies its strength), much less to bemoan its taste, but rather to suggest how it serves to ‘curtain off’ shit and death. For in lieu of images of flag-draped coffins, let alone of blown-apart bodies, we get these bows inveigling our support—which, of course, is less for ‘our troops’ than for this administration, whose adventures are not exactly in the troops’ best interests. Seen from this jaundiced point of view, the bows begin to seem more like collars that bind us sentimentally to the imperial project.13

It’s natural to desire comfort in the face of terror. I have no issue with Americans who sought and found comfort in these types of kitsch memorabilia. When the world feels horrible, it makes sense that someone would crave something easy, emotionally satisfying without the required labor of intellectual exercise.However, when kitsch paraphernalia is used to ignore reality, used to beautify evilness, used to simply ignore “shit,” often to the benefit of corporations or political regimes, this ceases to be an innocuous comfort.

Because kitsch relies on well-known tropes and patterns to elicit an emotional response from the observer, it operates on clear binaries. When we imagine kitsch, we often picture the saccharinely sweet or the morally righteous. But there is another side to kitsch, the depiction of something blatantly evil, disgusting, and wretched. Kitsch operates in black-and-white thinking, an overly simplified idea of the world. Linstead writes, “Kitsch proposes that the world is, in fact, as we want it to be (or, alternatively, as we fear it is, in certain respects).”14 Kitsch not only shows the viewer their idealized version of the world, one full of rainbows, flowers, and butterflies, but can also show them what to fear.

Kitsch will tell us what is good, what is bad, what we should fear, what we should strive for, and it will do this without requiring us to think or analyze; it is presented to us right there on a gaudy, ornate, gold-plated platter.

These two sides of the kitsch coin are captured well in the paintings of Jon McNaughton, one of the most well-known artists of the MAGA movement. Self-described as “America’s foremost conservative artist,” McNaughton himself confesses his work has no nuance. “American politics is filled with nuance and shades of grey, but I see the world through a prism of light and truth. My art reflects who I am and doesn’t use nuance or shades of grey to make my point.”15 This, at least, is true. His work depicts the world as a place of extremes; one is either purely good or purely evil. McNaughton’s pieces show no depth, relying on ham-fisted symbolism and the viewer’s emotional response. In other words, it is pure kitsch. So incredibly kitschy, in fact, that it could easily be mistaken for satire. As author Neil Fauerso so accurately describes, “McNaughton makes Thomas Kinkade-esque oil paintings of sentimentality so rich and thick it nearly crosses into the gonzo surrealism of early John Waters films.”16 Despite veering into this type of absurd sentimentality, McNaughton’s work is obnoxiously earnest.

One work that showcases the “good” or “ideal” side of kitsch is the painting “Teach a Man to Fish”. In a lush green garden scape, Donald Trump sits on a bench with a young man, a tackle box between them. Trump is holding a fishing rod as the young man, a college student, looks at the tackle box with fascination. His backpack is off to the side, a stack of books with the titles “Socialism” and “Justice Warrior” now discarded in favor of Trump’s wisdom.

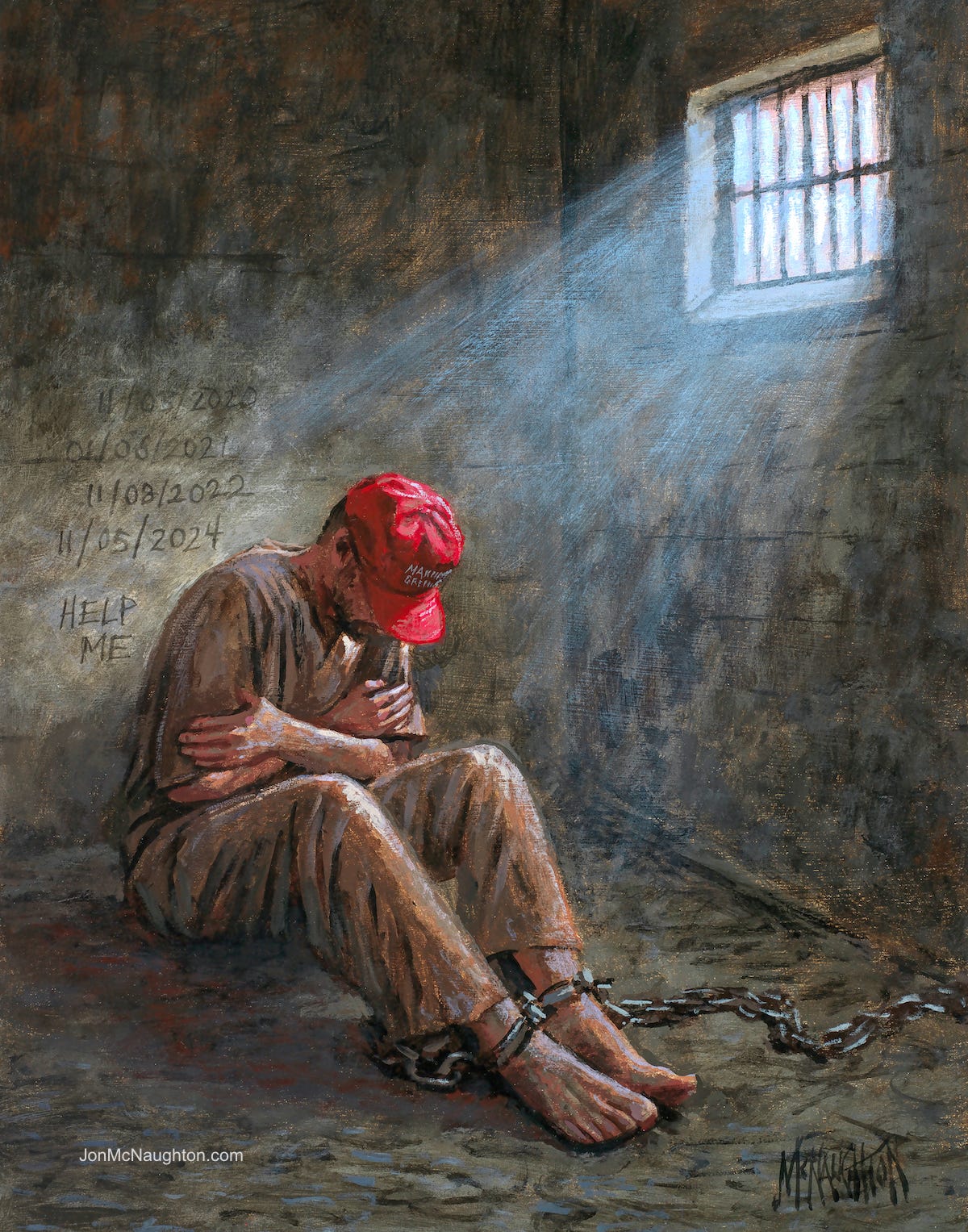

The second work, titled “Solitary Confinement,” depicts a prisoner chained up in a small jail cell, curled up on the cement floor. His face is concealed by a “Make America Great Again” red hat. A single window allows for a god-like light to shine into the man’s cell, illuminating his figure along with a set of dates and the words “HELP ME” carved into the walls of his enclosure. This work, McNaughton explains, was inspired by those arrested for storming the Capitol on January 6th and for the Americans who “feel that they have been denied their Constitutional rights and freedoms and are isolated and forgotten, in essence, placed in a solitary confinement.”17

These distinctly different works are both kitsch, not because of artistic style, but because of their content and rhetoric. “Teach a Man to Fish” depicts an idealistic version of the world a conservative might imagine—a nice white college boy pushing aside his “radical” books to learn about the art of fishing from a kind, manly father figure, an idealized trope of a good old American man (who just happens to be Donald Trump). It is the kind of image you can imagine someone looking at and touching their cheek, commenting, “Oh, how nice!” The subject matter is familiar, the title literally taken from a well-known proverb. The work might make one think of “the good old days” and has an air of simplicity and ease—the kind of world where your son is not educated in the ways of socialism and social justice and instead chooses to pursue something more conservative, masculine, and self-reliant. The artwork reflects the kitsch ideal, illustrating what a “good” world would look like, what the viewer could have, and what they should be striving for.

“Solitary Confinement,” on the other hand, showcases the other side of kitsch, a warning rather than an ideal. The viewer is meant to sympathize with the prisoner, sitting alone, chained and desperate. The single window of his cell floods him with a godly light, telling us that he is not bad, he is good, and how wrong it is that someone good could be treated so poorly. The viewer is meant to not only sympathize with the prisoner, they are also meant to feel outrage at his wrongful imprisonment, possibly even identify with him, sparking the fear of “what if…?” It is an image that would make someone “tsk” and shake their head, suggesting that this is the kind of world liberals want. “What kind of people would do something like this to a God-loving patriot?” they would ask.

These works, like all patriotic kitsch, are self-aggrandizing, narcissistic, and performative. They are shallow depictions of obvious tropes: the hero, the downtrodden, the villain. When I look at McNaughton’s artworks, especially pieces like “Solitary Confinement,” I can tell that he imagines himself as the figure he is painting. I can imagine him in his studio, sketching out the work and saying to himself, “Yes! Look at how sad and downtrodden this poor man looks. Look how persecuted my people are. God, I’m so tied down by the shackles of Liberal America!” I can imagine him patting himself on the back for creating a figure, a figure he identifies with, that looks so pathetic. There is almost a voyeuristic aspect to it, the sort of feeling you may get when you are sad that something happened to you and stop to think, “See! Look how broken up I am! I am clearly so upset, it is tearing me apart!” to no one in particular.

One of the most famous quotes regarding kitsch comes from Milan Kundra’s novel The Unbearable Lightness of Being. It reads,

Kitsch causes two tears to flow in quick succession. The first tear says: how nice to see children running on the grass! The second tear says: how nice to be moved, together with all mankind, by children running on the grass! It is the second tear that makes kitsch kitsch.

It is not the action of children running in the grass that is kitsch; it is the person seeing it and noticing how the action of children running in the grass makes them feel, or how it should be making them feel, and then admiring the fact that they feel moved that is kitsch. It is less about the actual object and more about the observer and how the object makes them feel. Of course, an object may be created for the purpose of stirring this emotion, but it still relies on the observer to feel the feeling. It is a fantasy of an emotion, a performance of sentimentality, letting the viewer feel good about themselves for having the feeling in the first place. It is patting yourself on the back for being humble, relishing in how upset you are by the evil in the world, telling everyone how you are really an empath because you just feel so deeply, all while being acutely unaware of the people around you.

As I have researched and read about kitsch, I have thought about my own attraction to it. Despite my arguments in this essay that kitsch is shallow and synthetic, I enjoy it as I enjoy pure camp—the excess and sentimentality, how gaudy it can be. I have questioned many aspects of what kitsch even means, and I have resolved to the usual and somewhat unsatisfying conclusion of “I know it when I see it.” I have begun to operate on the basis that there is not a single type of kitsch; rather, it is an umbrella term with various sub-kitsch categories. Unlike Hermann Broch, I do not believe that kitsch in and of itself is evil. That being said, I do believe it can easily lend itself to evil ends because kitsch does not ask the viewer to think before they feel. What changes kitsch from being simply kitsch to something more harmful is the intent and purpose behind it.Political kitsch not only relies on the viewer to feel the emotion it is trying to convey to be kitsch, it also relies on the artist having an explicit and expressed agenda.

When I am online and see a repost of some AI slop image the official White House X account posted of Trump enthroned and crowned king, or a schlocky Jon McNaughton painting, or a red, white, and blue Swarovski crystal-covered “TRUMP” clutch (only $550!), I feel an indescribable sense of schadenfreude, disgust, and awe. I feel almost… giddy, in a twisted way. I do not want to think it is because I view my own taste as “better,” but maybe it is through some odd lens of superiority that I can see these images and see them as over-the-top, ridiculous, even outright propaganda, or maybe the feeling I get is something else. I find a perverse joy in this type of kitsch, even if that is not what I am meant to be feeling. Either way, it is provoking an emotional response, and is that not, on the most basic level, what kitsch is meant to do?

Clemence Greenberg, “Avant-Garde and Kitsch” (Partisan Review, 1939), https://bpb-us-e2.wpmucdn.com/sites.uci.edu/dist/d/1838/files/2015/01/Greenberg-Clement-Avant-Garde-and-Kitsch-copy.pdf.

ibid

Matthew Rozsa, “Trump the Fascist Artist: How the MAGA Crowd Is Motivated by Aesthetics, Not Ideas,” Salon, December 5, 2020, https://www.salon.com/2020/12/05/trump-the-fascist-artist-how-the-maga-crowd-is-motivated-by-aesthetics-not-ideas/.

Kundera, Milan and Michael Henry, Heim. 1984. The Unbearable Lightness of Being. Harper & Row.

Linstead, S. (2002). Organizational Kitsch. Organization, 9(4), 657-682. https://doi.org/10.1177/135050840294008 (Original work published 2002)

ibid

Chris Lehmann, “The MAGA Aesthetic Is Beginning to Rot,” The Nation, March 11, 2024, https://www.thenation.com/article/politics/maga-aesthetic-trump-style/.

ibid

Catherine A Lugg, “Political Kitsch and Educational Policy.,” April 1998.

Eric Gibson, “Why Dictators Love Kitsch,” Wall Street Journal, August 10, 2009, sec. Life & Style, https://removepaywalls.com/https://www.wsj.com/articles/SB10001424052970204908604574336383324209824.

Marita Sturken, Tourists of History: Memory, Kitsch, and Consumerism from Oklahoma City to Ground Zero 9780822390510 (Duke University Press, 2007), https://dokumen.pub/tourists-of-history-memory-kitsch-and-consumerism-from-oklahoma-city-to-ground-zero-9780822390510.html.

John Frow, “Kitsch Politics,” Cultural Studies Review 14, no. 2 (September 2008): 200–204.

Hal Foster, “Yellow Ribbons,” London Review of Books, July 7, 2005, https://www.lrb.co.uk/the-paper/v27/n13/hal-foster/yellow-ribbons.

ibid

“The Artist - McNaughton Fine Art,” accessed May 26, 2025, https://jonmcnaughton.com/the-artist/.

Neil Fauerso, “The Aesthetics of MAGA,” Glasstire (blog), August 12, 2019, https://glasstire.com/2019/08/12/the-aesthetics-of-maga/.

“Patriotic - Americana - Solitary Confinement - McNaughton Fine Art,” accessed May 26, 2025, https://jonmcnaughton.com/solitary-confinement/.

Whopper of an article. Thanks for all your time and hard work this was an absolute treat.

very cool and well-argued article!! another interesting aspect of kitsch you made me think about here is its relationship to the capitalist drive for growth + reproduction: its inseparable ties to mass industry, its need for exactly replicable pleasures, immediately digestible "types", the creation of a prefab world which left to its own devices turns into the kind of sludgy horror vacui of a kinkade painting... i think there's something perversely exciting about kitsch's sheer nonstopness given the boxy minimalist hell that's been the norm in stores, homes and web ecosystems for a decade plus now-- probably the same impulse keeping y2k nostalgia so prominent? it appears that for the right, capitalism has not yet lost its erotics.